“Given the disparity and inequity in education, methods and methodologies, change is not just an educational imperative but a moral one.”

At the start of the lecture, Peter D’Sena asked participants: ‘What does decolonising the curriculum mean to you?’. These are the answers.

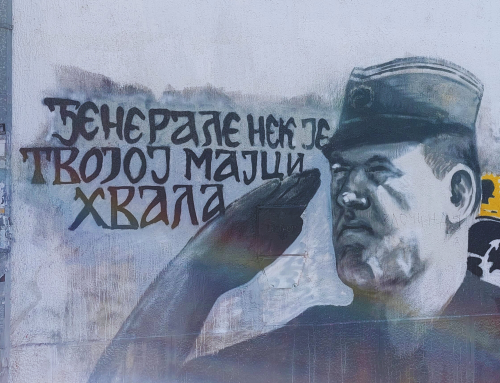

In 2015, students at the University of Cape Town, South-Africa, called for the statue of Cecil Rhodes, the nineteenth-century British coloniser, to be removed from their campus. Their clarion call, in this quick spreading #RhodesMustFall movement was that for diversity, inclusion and social justice to become a lived reality, the full gamut of educational provision should be challenged, and schools and universities decolonised.

But before understanding how we can decolonise education and the curriculum, it is crucial to understand our colonial past and coloniality. In EuroClio’s Keynote Lecture of the Decolonising Webinar Series, Prof. Peter D’Sena gave an introduction to decolonising the curriculum by focussing on the historical dimensions of colonialism and coloniality.

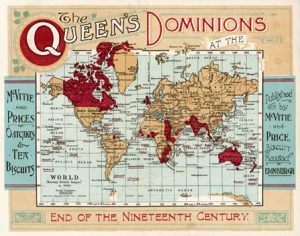

Colonised lands and commodities: the creation of a global economy built on blood and suffering

Prof. D’Sena explained how the colonised world was formed with the help of the Black Atlantic. Slavery was a complex part of the colonial world. The implications for humanity were enormous. A vast number of people died during the middle passage, the forced passage from enslaved Africans across the Atlantic to the New World. Ships were organised to carry people like cargo and people were treated like cattle. While the exact number of people transported remains unknown, estimates surpass 10 million. What we do know is that on the passage people were deprived of their language and liberty and were subjected to brutality. The Black Atlantic displaced so many people that we lost their voice. Once people arrived in ports, they were separated from their families and sold. They were deprived of their cultural identity. Finding the voice of those who were enslaved has proven very problematic, only rescued by a number of historians in the 20th century, most notably by Trinidadian Historian C.L.R James in the Black Jacobins (1938).

World map of the Queen’s Dominions, late 19th Century. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Commodities formed an important part of the colonised world. During the Columbian exchange, one of the greatest gifts of the Europeans to the Americas were smallpox, measles, typhus and cholera. Colonies were for and about exploitation. The blood and suffering of slaves and indigenous people fuelled a consumer revolution in Europe. This led to a global economy with ongoing vestiges today. Apart from an exchange of commodities, coloniality also meant the exchange of ideas. Underlined by Rediker & Linebaugh (2000), ships carried ideas of revolution. In Europe this established itself in a dependence on tobacco and coffee, the establishment of cotton fed industrialisation, and an example being how mahogany changed people’s tastes.

Prof. D’Sena explained how indentured labour has been relatively ignored when talking about coloniality. Indentured labour, a form of labour in which a person works without payment for a set amount of years, has existed throughout history. When Britain abolished slavery in 1807, and in the colonies in 1833-1834, new forms of slavery were introduced. From 1838 to 1920 indentured labour was a system which helped to make the plantations work. Transoceanic movement meant more cultural change and hybridity as well as greater complex identities. Prof. Peter D’Sena drew upon his own heritage explaining how his grandfather had been an indentured labourer, having travelled from Calcutta to Trinidad and Tobago. He subsequently fled, becoming the first East Indian to settle in Barbados (Nakhuda, 2013).

Colonised bodies and minds: the pseudo-science of race and epistemicide

When talking about colonialism, the pseudo-science of race developed in the 17th and 18th century, is an important aspect to consider. It led to a theory of scientific racism and the dissemination of an ideology of racism which would come to underpin exploitation and supremacy. This pseudo-scientific racism culminated two centuries later – in the late 19th and early 20th century – in the eugenics movement. This led to a classification of human beings, with peoples ranked according to physical features. In European culture it led to an ubiquitous notion of beauty. People of colour were objectified and hypersexualised. Many of the racist stereotypes that emerged in the 17th and 18th century still exist today. This ideology of racism was fuelled by scientific research and by fear and othering, justifying the treatment of people in plantations and beyond. Pseudo-science and the classification of human beings helped underpin the idea of race and colour aiding the establishment of racial hierarchies. In the colonies people would ‘pass’ as white (see also EuroClio’s recent review of Nella Larsen’s “Passing” for more on this subject).

The systemic marginalisation, as well as the destruction of the knowledge systems of indigenous and colonised peoples, is called epistemicide. At the very least it is the assimilation of those knowledge systems into the dominant knowledge system and values of the colonisers. One vehicle for domination was language and education. The concept of ‘colonial minds’ helps us to understand the key ambition of the colonisation agenda. Colonising the mind refers to colonising peoples’ culture, their being, their belief, and way of thinking. The implications of epistemicide are very present in today’s society.

Decolonising the Curriculum: a coalescence of old and new conversations

Removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes from the campus of the University of Cape Town, 9 April 2015. Licensed under CC2.0 via Flickr. Image by Desmond Bowles.

In previously colonised places, globalisation and coloniality are merging to maintain Western dominance. Rather than post-colonialism, Prof. D’Sena described how neo-imperialism remains in place. Thinking of the decolonisation debate presents a number of dilemmas. Are we willing to look past misdemeanours? Reparations? Do we need to press the ‘reset button’? Is it even possible to dismantle the system built upon colonisation? Can decolonisation be seen as a spectrum? What should we think of doing for ourselves, for our society, for our curriculum?

Concerns have long been voiced by both academics and students about curricula dominated by white, capitalist, heterosexist, western worldviews at the expense of the experiences and discourses of those not perceiving themselves as fitting into those mainstream categories. In recent years these discussions have been brought together under the banner of decolonising history. The Rhodes Must Fall Movement meant more than getting rid of a statue and reaches back to movements of Black Power, civil rights, Négritude and many more. The movement came to be quickly connected to the Black Lives Matter Movement which spread across the world. The emerging conversations may have reached the news because protests were disseminated and statues were ‘attacked’ as part of symbolic attacks. The movement is about much more, about ourselves, about our own position, biases, and our own white privilege.

Education is still dominated by the values of scholarly activity determined in the West. Countering epistemicide, is going to be enormously challenging as so much has been drowned by the process of coloniality and colonialism (Sousa Santos, 2018). In our quest to decolonise the curriculum, it is not just our own view that matters but also that of our students. Prof. D’Sena urges educators to think of ways to involve students in the cocreation of knowledge. It is important to talk about the ideology of racism and the complex scheme in which not just our belonging but also our minds and bodies were shaped by coloniality.

Initiating change

“The hardest thing is thinking about our own positions, about our own biases, about our own privileges, if we are to think about decolonising the curriculum in our own practice, we have to think about our own conscious and subconscious biases in both witting and unwitting practices.”

During the lecture, participants took a moment to reflect on their practice and consider ways in which they can be part of the change they would like to see. We would like to invite you to do the same, add your commitments to our collective padlet. You can find it at this link: https://cutt.ly/decolonise-history.

About Prof. Peter D’Sena

Peter D’Sena is Associate Professor of Learning and Teaching at the University of Hertfordshire and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research. His key contributions to history education are borne from his enduring commitment, over four decades, to equality and inclusion. As a writer of the revised National Curriculum in the late 1990s he championed the introduction of black history; now he continues to lecture and write on decolonising the curriculum. As the HEA’s National Lead for History he organised the revision of the Benchmark Statement and created innovative resources for those ‘New to Teaching’. He is a fellow of the Historical Association, a principal fellow of the HEA and last year he was elected to be the first President of SoTL’s European branch for History. Professor D’Sena is also Vice-President and Chair of the Education Policy Committee at the Royal Historical Association.

Resources suggested by Prof. Peter D’Sena for exploring ‘decolonising the curriculum’ can be found here.

Image banner: Removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes from the campus of the University of Cape Town, 9 April 2015. Licensed under CC2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Image by Desmond Bowles.