In this book, Judith L. Pace examines the work of four teacher educators from Northern Ireland, England, and the USA as they show their graduate students’ different approaches to teaching about controversial topics. The author claims that the area of preparing preservice teachers to teach controversial topics is not sufficiently developed. This is why one of the key questions in modern teaching is “How can new teachers learn to teach controversy in the realities of the charged classroom?”

The book also compares how the teaching of controversial issues is interpreted in different national and educational contexts. It demonstrates how risk-taking can be contained, constrained, and supported in a wide variety of classroom and school settings. A limitation pointed out by the author herself is that the research centred on national contexts of countries with less restrictive political systems.

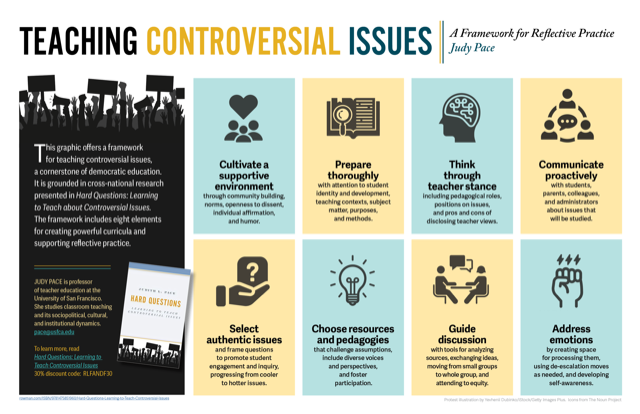

In the beginning, the author highlights the importance of dealing with controversial issues and introducing them in school lessons. Referencing various sources, she points out the lack of adequate preparation of beginner teachers for exploring controversial issues with students. The introduction of conceptual and practical tools that teachers can adopt in the classroom, modelling the use of these tools and creating opportunities to rehearse them are all crucial for preparing to deal with controversial issues.

In the following chapters, the author presents four different teacher educators and their graduate students from Northern Ireland, England, and the USA.

- Mark Drummond, a teacher educator from Northern Ireland and his Citizenship and History courses. Mark has encouraged his preservice teachers to try different tools such as walking debate and role-play, political murals, and analysis of primary and secondary sources. Student teachers faced various challenges such as students’ reactions to controversy, their own emotions sparked by teaching controversial issues and limited time. But they experimented with various ways to get post primary students to consider different perspectives on history, human rights, and politics. Mark’s preservice teachers learned the most from his example and his principles of practice, such as developing a trusting classroom environment, using evidence to think critically, and using rich resources and dialogic pedagogies.

- Paula Barstow, a teacher educator from Northern Ireland and her Citizenship course. Paula stresses that potential risks of teaching controversial issues can be contained through careful planning proactive communication, and thorough reflection to keep both students and teachers safe. Teachers need to use inclusive discussion such as a walking debate, deliberation (Structured Academic Controversy), carousel conversation and written conversation that encourage all students to participate. Preservice teachers reported they learned the most from structured small group activities, careful curriculum design, preparation for teaching, and exploration of the teacher’s role. The student teachers’ efforts were constrained by limited time and low status of citizenship, the pressure to cover curriculum and mentor teachers who interfered with their autonomy.

- Ian Shepherd, a teacher educator from England and his History course. Ian’s approach to preparing preservice teachers to teach controversial issues chose to embed the practice in class sessions rather than addressing it discretely. His idea was that everything in curriculum had the potential to be sensitive or controversial. The overall approach to preparing preservice teachers was to integrate controversial elements in course sessions and assignments. He believed that when preparing to teach controversial issues, preservice teachers first need to develop their subject matter knowledge, be willing to experiment with provocative sources and experimental methods, and to reflect on teaching and learning in their classroom. Preservice teachers learned that teaching controversial issues first demands structuring a progression of conceptual change in which the teacher elicits students’ prior knowledge, gets students to deal with inquiry questions that often are moral, and helps students to arrive at new understandings. Although student teachers were constrained by their timetable, curricular demands, and traditional school culture, they were supported by SoW (scheme of work) assignments, encouragement from peers, mentors, and department heads.

- Liz Simmons, a teacher educator from the USA and her Social Studies course. Liz believed that teaching controversial issues and teaching difficult history are distinct practices, but both are served by making classroom discussion the central pedagogy and content of a teacher preparation course. Tools that Liz introduced to her students were Structured Academic Controversy, Socratic seminar, Town Hall, and Case Study, as well as curricular programs such as the National Issues Forum and Brown University’s Choices. Liz stressed that preservice teachers need explicit modelling of discussion facilitation, opportunities to practice discussion preparation and facilitation, and feedback as well as self-assessment of their practice. Liz’s students most appreciated practice teaching and discussion of issues in the methods course. They used Structured Academic Controversy and other discussion methods in their teaching, but in one case, teaching controversial issues was constrained by the teacher’s professional learning community and evaluation of first year teachers.

In conclusion, the author emphasises that all four teacher educators, although working in different contexts and school subjects, emphasised three cornerstones for open classroom environment – issues content, pedagogical methods and tools for modelling democratic inquiry and discourse, and creation of a supportive atmosphere. They taught eight strategies to prepare novices for contained risk-taking: cultivation of warm, supportive classroom environments; thorough preparation and planning; reflection on teacher identity and roles; proactive communication with parents, other teachers, and administrators; careful selection, timing and framing of issues; emphasis on creative resources and group activities; steering of discussion and dealing with emotional conflicts. Preservice teachers agreed good preparation of lessons, choosing right pedagogical methods and tools, and creating supportive atmospheres were crucial for addressing controversial issues. The biggest constraints they had were time restrictions, mandated curricula and exams, and lack of support in schools.

Judith L. Pace believes that the book brings new knowledge on how to strengthen practices at all levels of schooling. She believes that addressing controversial issues would be most impactful with students from different communities. Also, her research indicates that more structured university involvement during student teaching could be a vital source of support. Ideally, teacher educators should be working with mentor teachers in the school to jointly support novices.

I agree with most of the conclusions the author wrote in this book. Teaching controversial issues is important for strengthening democracy, especially in a time when manipulation of facts and violation of human rights is done on a daily basis. But it can only be done with well-educated and trained teachers who have support in their schools and communities. A responsible society should do its best to support young teachers. Also, teacher educators should have a bigger role in guiding the teachers not only through their preservice time, but also during the first few years of their career. The research presented in this book shows mainly conclusions derived from the teaching in Northern Ireland, England and the USA, but in many cases, they can be linked to other countries in Europe. In my belief, it is very important to know who you are teaching. However, although controversial issues may vary from country to country, they should all be addressed in a way to strengthen democracy.