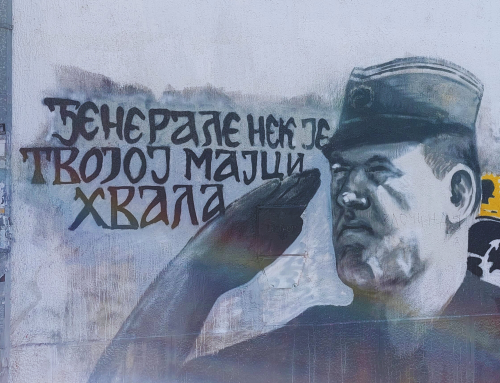

Looking back at her illustrious career, recently retired Professor Maria Grever can not only be proud of her achievements, but also rest assured that her work is especially relevant today. Emeritus Professor of Historical Culture at Erasmus University Rotterdam, Professor Grever and her team have relentlessly investigated how people deal with the past, including what and why they remember and celebrate. Therefore, she has a lot to say about the current destruction of statues related to the Black-Lives-Matter movement taking place around the world. Interviewed by Erasmus Magazine shortly after the launch of her latest book, Onontkoombaar verleden (Inescapable Past), she warns against the total eradication of monuments and statues that constitute testimonies of past injustice: destroying statues is no medicine against racism! Moreover, without such evidence, modern societies would forget, instead of facing, their mistakes. But, she stresses, we cannot expect monuments alone to tell the whole story. While on-site explanations can help contextualisation, it is crucial to improve history education in schools so that the young generations are equipped to critically approach this material heritage, and to understand the controversies surrounding it.

History education is a topic dear to Professor Grever. Once a high school teacher herself (1980-1984), as an academic she has relentlessly advocated increased co-operation between the two sectors, and also the domain of heritage institutes. In order to further research on this relationship, she founded in 2006 the Center for Historical Culture, and conducted extensive investigation into processes of canonization in the historical discipline and history education. Another research project focused on how history education can benefit from a critical and dynamic approach to heritage related to the Transatlantic slave trade and WWII /Holocaust. Recently, she co-investigated the opportunities and risks of popular representations of modern war heritage as informal ways of history learning. In August, the bilingual Journal for the Study of Education and Development (Infancia & Aprendizaje) will publish a Special Issue edited by Maria Grever and Karel van Nieuwenhuyse on Popular uses of violent pasts in educational settings ( Los usos popularos de pasados violentos en entornos educativos): https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/riya20/current.

History education is a topic dear to Professor Grever. Once a high school teacher herself (1980-1984), as an academic she has relentlessly advocated increased co-operation between the two sectors, and also the domain of heritage institutes. In order to further research on this relationship, she founded in 2006 the Center for Historical Culture, and conducted extensive investigation into processes of canonization in the historical discipline and history education. Another research project focused on how history education can benefit from a critical and dynamic approach to heritage related to the Transatlantic slave trade and WWII /Holocaust. Recently, she co-investigated the opportunities and risks of popular representations of modern war heritage as informal ways of history learning. In August, the bilingual Journal for the Study of Education and Development (Infancia & Aprendizaje) will publish a Special Issue edited by Maria Grever and Karel van Nieuwenhuyse on Popular uses of violent pasts in educational settings ( Los usos popularos de pasados violentos en entornos educativos): https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/riya20/current.

Over the years, Maria Grever has been critical of a top-down canon for history education. In her view, such a canon fails to stay up to date with the latest research findings, particularly regarding multiple perspectives on the past. For example, while in the past few decades historiography has grown more and more interested in the history of women and slavery, it has been challenging to incorporate these topics in school curricula. Nevertheless, Professor Grever is quite satisfied with the current situation in the Netherlands, where there is growing interest among academic historians into history instruction and historical culture in general. Young generations of professional historians are now keen to engage with their subject in new ways, confident that their research will have a positive impact on society. But the drafting of the Dutch canon has not only benefited from the contribution of academia: the involvement of local museums and heritage associations has produced a variety of (counter-)canons built on regional particularities, including the history of migrants and colonialism.

Over the years, Maria Grever has been critical of a top-down canon for history education. In her view, such a canon fails to stay up to date with the latest research findings, particularly regarding multiple perspectives on the past. For example, while in the past few decades historiography has grown more and more interested in the history of women and slavery, it has been challenging to incorporate these topics in school curricula. Nevertheless, Professor Grever is quite satisfied with the current situation in the Netherlands, where there is growing interest among academic historians into history instruction and historical culture in general. Young generations of professional historians are now keen to engage with their subject in new ways, confident that their research will have a positive impact on society. But the drafting of the Dutch canon has not only benefited from the contribution of academia: the involvement of local museums and heritage associations has produced a variety of (counter-)canons built on regional particularities, including the history of migrants and colonialism.

While enthusiastic about the co-operation of teachers, historians and museums, Professor Grever rejects the interference of governments and politicians into the contents of history education. These actors tend to promote a single and frozen narrative of past events focusing on the formation of the nation, thus often overlooking world history and excluding the perspectives of minority groups. They fail to grasp the complexity of the subject, overlooking the importance of critical discussion, and expecting students to simply acquire knowledge of facts without engaging in their interpretation. In order to guarantee a high quality of history education practices, it is necessary not only to resist this kind of interference, but also to allow teachers the freedom to deviate from the prescribed canon to organise activities fostering discussion. For example, Professor Grever recalls that once when she was still a teacher, she organised a debate about the conflict between Israel and Palestine. It took her a lot of effort and planning as she had to prepare the students in advance, find appropriate material and effectively chair the debate. In the end, it was a very positive experience for her and the students. Hence, she encourages teachers to organise this kind of activities. However, she is well aware of the difficulties that teachers face, such as the constraints of curricula and the inadequacy of textbooks. And it is this awareness that makes Professor Grever a firm supporter of EuroClio.