EuroClio Project Manager Andreas Holtberget had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Angela Bermudez on the subject of her recent study on the normalization of violence in history textbooks. Dr. Bermudez is a researcher at the Center for Applied Ethics at the University of Deusto (Bilbao, Spain) where she investigates how history education in different countries fosters or hinders a critical understanding of political violence. She is the author of several papers on civic and moral education, history education, and memory. Her recent working paper titled “The Normalization of Political Violence in History Textbooks: Ten Narrative Keys” is part of a series sponsored by the Alliance for Historical Dialogue and Accountability, Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights, and Dialogues on Historical Justice and Memory.

There lies a great paradox – most textbook content centers around violent experiences and yet very little of this violence is the subject of critical reflection.

Could you please tell us a bit about yourself, your research, and how you got interested in the topic of education and the normalization of violence, in particular?

I grew up in Bogota, Colombia, and, in many ways, I think that marked the beginning of my interest in issues related to political violence – it is a place that can serve as a lab for all kinds of experiences and reflections on various types of violence. However, I didn’t actually begin to focus on this topic academically until later on. I was studying history education when I received a scholarship to study in Spain for a year and a half. While I was here, I had the good fortune to meet Professor Mario Carretero and some of his doctoral students. They got me hooked on studying the development of cognitive historical thinking skills. We considered questions like “How do young people learn to think in complex ways about something like the past which isn’t tangible and which they cannot experiment on in the classroom?”

Following graduation, I returned to Colombia where I moved away from history and got more involved with projects that centered around moral development in civic education. I quickly connected this new focus with the experiences of violence in the supposedly oldest democratic state in Latin America. Compared to other Latin American countries, Colombia had a very short and unusual dictatorship. Nevertheless, the country has an extremely violent history. This raises all sorts of questions about the linkages between violence, democracy, and citizenship.

I went on to do my Ph.D. at the Harvard Graduate School of Education where I wrote my dissertation on how young people engage in discussing controversial issues – politics, racism, police brutality, etc. I worked with Facing History in Ourselves, a non-profit that develops educational material on prejudices and injustice in an effort to empower teachers and students to think critically about history and to understand the impact of their choices. This brought me back to my previous interest in education and violence, but more from an ethical and critically thinking perspective.

When I moved to Spain 8 years ago, I had the opportunity to rethink and redefine my research agenda. I began analyzing how different means of history education contribute to the normalization of violence, or conversely, to the promotion of a critical understanding of violence. The role of history textbooks has captured my attention to the extent that it has because – despite being used in the classroom less and less – what is stated in them is a clear depiction of the dominant historical narratives of a country. Textbooks can reflect the politically official narratives, the counter-narratives in academic debates, and/or public discourse more broadly.

Can you speak about the research you have been conducting on textbooks in Spain, Colombia, and the United States?

Our analysis focused on how textbook narratives represented the violence intrinsic to nine different episodes of the violent past of these countries. For each topic, we looked at approximately four different textbooks and one or two alternative, non-conventional teaching resources, such as those developed by NGOs or research centers or that have different pedagogical approaches. We found that there is a striking difference between conventional textbooks and other resources and that a persistent pattern of normalizing violence exists across textbooks, topics, and countries. Despite the abundant references to violent events, violence as such is rarely discussed or made the object of explicit analysis. Quite the contrary, violence is normalized through discursive processes that define what is emphasized and what is marginalized, what is connected and disconnected, and what is silenced. We identified ten narrative features that describe interlocking mechanisms by which historical accounts manage to describe violent events and processes while precluding any reflection about its roots, causes, consequences, and alternatives. There lies a great paradox – most textbook content centers around violent experiences and yet very little of this violence is the subject of critical reflection. You talk about violence, but you don’t see its victims, causes, or consequences or the alternatives to it.

What you encounter in textbooks are stories of violence without pain.

Can you provide an example of violence made invisible in a textbook in a rather striking manner?

First, let me explain what I mean by ‘normalizing violence’. This is a discursive process. It is a way of turning something that is socially constructed into something that is natural or inevitable – in other words, normal. Something that is normal is something that doesn’t surprise us or deserve our attention. It is not worthy of becoming the object of our critical reflection. Normalizing is a way of talking about something, but presenting it as something that you can or should take for granted.

Now the narrative key example you asked for. Apart from a few exceptional topics, the Holocaust being the most evident example, history textbooks contain very few references to victims in episodes of violence across time. In some instances, a chapter that focuses on a war will mention consequences as human casualties or refer to a demographic loss. You might get a number and maybe a few more details, but there is very rarely a depiction of the experience or perspective of the victims. Of course, if the episode we are talking about is one in which “I am the victim” then there are more references to “we were the victims.” However, even this reference to ourselves as being the victims does not depict the experience of victimization as such. What you encounter in textbooks are stories of violence without pain.

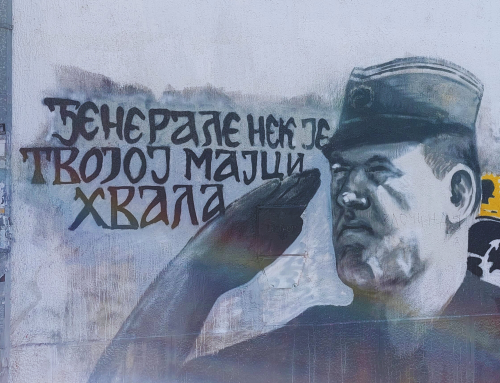

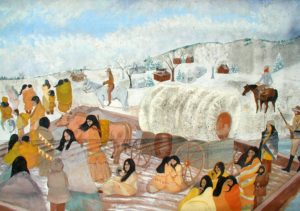

Another narrative key that subtly normalizes violence is the concealment or obscuring of human agency. You read descriptions of historical events that involve a lot of violent action, but with little reference to who instigated it. It’s not a matter of assigning blame – which can be complicated – but rather one of understanding that violence is not a natural phenomenon. You have to distinguish between impulsive aggression and political violence. Political violence is systematic and instrumental. There are individuals, collectives, and institutions making decisions to use violence – to use other human beings as means to an end – rather than take an alternate non-violent course of action. You’ll read things like “War broke out.” This needs to be at the heart of ethical reflection. On the topic of the Trail of Tears in the US, you have accounts of how Native Americans marched from one place to another during a cold winter and many died. But who made the decision to have them march at that time of year? Why didn’t they have blankets or minimal medical resources? The same framing is applied when considering any episode of violence. What we witness is an obscuring of agency – it is sent to the back of narrative. This results in stories of violence with no blame and no responsibility.

A narrative key we most consistently see across textbooks, topics, and countries is the near-absolute silence on alternatives to violence and the individuals and movements who supported these alternatives. It is not as if there was a dearth of opposition to violence. In a large number of episodes of the violent past there was active opposition to violence and advocacy for nonviolent solutions to conflict, and yet not much, if anything, is said about them. So how does that play into the normalization of violence? Well, if no one opposed the use of violence, maybe that was the only way the episode could have played out. There were no alternatives.

One final example of a narrative key that serves to normalize violence is the omission of the benefits derived from violence. Who gains? Of course, you’ll read “We gained independence,” but that’s a social goal. What I mean here is who, in terms of individuals or sectors of society, gains from the industry of war (or other types of violence) at a political or economic level? Omitting these massive industries and contested interests in society makes invisible the way in which violence can be a strategic means to achieve something and not a natural and inevitable response to conflict.

The issue is not that we are stuck with textbook narratives – we are stuck with social narratives. We are stuck with a social tendency to normalize violence.

If textbooks make violence broadly invisible by trivializing and normalizing it, what can we as history educators do to counter this, especially if the countries we work in are required to follow a prescribed list of topics and textbooks?

Let’s recall two things I mentioned before. Normalizing means taking something out of the area of our reflection. It’s turning an episode of violence into something that is natural and, therefore, unproblematic, so that we don’t reflect on it. We can still follow the prescribed topics and resources, but in order to counter the normalization of violence, we must raise questions that transform what has been normalized into something that demands critical reflection. We must call attention to issues and individuals who have been silenced and call attention, precisely, to the fact that they have been silenced.

So, okay, we’re reading this textbook account with our students. This narrative relies on ways of telling and silencing that have consequences. So, I want to call the attention of my students to this and ask – Who were the victims? What was their experience? Did anybody oppose what happened to them? Those questions can turn into projects, assignments, or debates. Additionally, the more you tie this to topics of more recent history, the more students can reference things from their own context. Of course, I’m not saying this is easy and isn’t the source of many controversies, but if you have the minimum conditions of safety, even if it’s controversial, for many students this is kind of discussion can serve as an oasis – you’ll create a space for them where these things can be talked about in careful, caring, and reflective manners, rather than in absolutes. At the end of the day, though, the issue is not that we are stuck with certain textbooks. We are not stuck with textbook narratives, we are stuck with social narratives. We are stuck with a social tendency to normalize violence.

In another article, you make a point that museums face different or less pressure than history textbooks authors or curriculum designers when curating. Could you please elaborate on what you mean? Is it a useful tool for history educators to make use of museum exhibitions?

Yes, absolutely. Museums, of course, are also sites of political discourse. Both schools and museums were, in the late nineteenth century, developed precisely to mold the minds of citizens and construct the idea of the nation. Museums do, however, have some general advantages over textbooks. One of the dynamics that restricts and impoverishes historical representations is the rise of standardized, external assessment. Textbooks and teachers can’t go into greater depth and discuss subtle, marginal, or controversial elements of history because they have to cover content for an assessment. Museums are far less regulated in terms of content. There is no mandated curriculum and no examination on your way out. You can have thematic museums and museums that make use of technologies inaccessible in the classroom that appeal more to the experience of emotions and textures of events in the past. A lot of what gets sent to the background of narratives that normalize violence is the texture of the experience of victims and the proponents of non-violence. Of course, you also have a lot of museums that celebrate war and heroic actors that represent the violent past similarly to textbooks, but you also have the emergence of memorial museums and sites of conscience whose mission is to convey a history that has been silenced and develop a critical understanding of the past.

Wouldn’t you say that given the national and international prominence of an episode like the Spanish Civil War, 80 years later it is reasonable to expect a national museum on the event to exist? There is no such thing.

The role of sites of conscience and memorial museums is very interesting. I was hoping you could speak a bit about the Valley of the Fallen and the recent memory laws that were passed. How do you see things developing in Spanish society more broadly?

If you follow the debates around memory and memory laws (passed in 2007) you’ll notice that socially, politically, and culturally there is a very profound silence about the Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship. Academic research, literature, and movies aside, socially – as in at the kitchen table, in public spaces – there is very little conversation and discussion about these topics. That silence – imposed during the dictatorship for obvious reasons – was maintained during the democratic transition, in part to not rock the boat at a time when political parties and social organizations were invested in figuring out how to operate together in the new democratic system. Politically, you can understand the pressure, but this “democractic silence” has now lasted even longer than the dictatorship itself. It’s been 40 something years and there’s still very little conversation about these topics. There has been a very vibrant and very important interdisciplinary initiative involving victims’ families and scholars around the exhumation of bodies from mass graves. This has ushered in a movement to recover memory, but it is still limited in terms of granting the wide public opportunities to engage with history in alternative ways.

People argue that these conversations are too uncomfortable, but do we ask if silence is comfortable for those who are told to keep quiet?

So do you think it was a mistake not to speak about these episodes of violence during Spain’s democratic transition?

I do tend to think it was a mistake, but I understand the political context and the need that many felt not to reopen wounds. There are many post-conflict contexts, like Rwanda, where a moratorium has been established. At the same time, I grew up in a country (Colombia) that has experienced ongoing violence and it is not as if we can stop talking about it. We need to be able to address these experiences reflectively. You begin to see other troubling political and ideological implications of silence there. People argue that these conversations are too uncomfortable, but do we ask if silence is comfortable for those who are told to keep quiet? In the case of the Spanish transition, this sort of socio-cultural silence was partly fueled by the idea, the fear, the myth, that if we talk about what happened, it will give rise to another civil war. That fear was later manipulated. This becomes more evident when you consider the fact that there has been no judicial or political process to prosecute any of the people responsible for crimes during the dictatorship and that many of the political and economic bases of the Franco regime continue to exist in the political and economic system today. Then the idea of sustaining that silence and not rocking the boat gains a new dimension. It is no longer simply “That was emotionally difficult. Let’s heal first and then address it.”

Wouldn’t you say that given the national and international prominence of an episode like the Spanish Civil War, 80 years later it is reasonable to expect a national museum on the event to exist? There is no such thing. There are a small number of regional museums and memorial sites – the Museum of Exile in Catalonia, the Peace Museum of Gernika (on the bombing of Gernika), one for the Battle of Ebro – but there is nothing akin to a general, national museum on this watershed event.

I wanted to touch on one last issue. It’s your other recent research. I understand that you are collecting testimonies from people who were involved with violent organizations like ETA in Spain and the Farc in Colombia. I’m really intrigued by this. Where is this research taking you and how will you continue with it?

That is a brand new project that we’re beginning to work on with an interdisciplinary team at the Center for Applied Ethics. I think it’s a fascinating and necessary initiative. We aim to collect life histories and interviews from people who were involved with groups that espoused the use of violence for political reasons, but later on renounced it. That is, individuals who at different points in their trajectories began to think differently about violence, to question it, and ended up renouncing it. What led them to that change may be very different – the experience of being imprisoned, the implications for their families, spiritual events, or political and ethical transformations. Our question here is how these people establish a relationship with violence, both in connecting with it, justifying it, and espousing it, but also in renouncing the use of it? What are those seed points, experiences, and reflections that transform their understanding and belief in the legitimacy of violence? There are many layers to this analysis, but the ultimate purpose is to develop educational resources for peace education that encourage people to think critically about violence.

Violence can be very seductive. We think it is a good idea to hear from those who were once seduced why they don’t want to be involved with it anymore. This can be a rich resource with which we can rock the boat, shock, and provoke critical thought in young people, but we are only just beginning.

I look forward to seeing the final results! Best of luck with funding and the study. Thank you for taking the time to speak with me today.