One of a teacher’s worst nightmares is when a classroom explodes into a heated argument that gets out of control. This is possible in all contexts and for various reasons; some instances are predicable, while others are completely unexpected. EuroClio has been exploring these issues with the ongoing Learning to Disagree project, with resources available in March 2020.

The Evens Foundation and The Flemish Peace Institute called a research meeting May 23-24 2019 to dig into the difficulties surrounding controversy and polarization. As part of my research traineeship at EuroClio, I was asked to present the Learning to Disagree project and parts of my master’s research at Erasmus University on controversial and sensitive history in a Dutch context. Here I will discuss some of the most important findings from that meeting.

Dealing with Controversy and Polarisation in the classroom

Initiator of the meeting and driven by his role as senior researcher at the Flemish Peace Institute, Maarten Van Alstein, wrote Omgaan met Controversie en Polarisatie in de Klas (Dealing with Controversy and Polarisation in the Classroom). Based on his research in the Flemish educational context, Van Alstein has developed a “scenario based approach” that may help teachers to deal with emotive and sensitive topics in the classroom. He discusses how in Belgium, and across the globe, students are being pulled to more extreme views with more strongly held positions that makes it more difficult to teach or predict when controversy may occur in the classroom. He distinguishes three different scenarios:

Scenario one: “A Classroom in Turmoil” describes a situation where a classroom explodes due to insensitive or inflammatory remarks. In this situation, depending on the teachers and students present in the classroom, a teacher must decide what to do quickly. There are pros and cons to removing a student from the class, cutting-off discussions, encouraging further discussion or probe a student for a particular response. Removing a student from the classroom may cease the undesired comments from the discussion, but it also limits that student’s ability to engage in more perspectives. There may be a fear of allowing a student to remain will only amplify the insensitive or undesired remarks, although probing a student for why they hold a particular viewpoint can allow for debasing their comments. Van Alstein states that in a polarized classroom teachers should aim for the middle, less vocal students by providing arguments based upon reason and evidence. These are the students who do not have cemented beliefs and may potentially be persuaded by the more radical classmates.

Scenario two: “Controversial Topics in the Curriculum” focusses on topics from within the curriculum that are perceived as controversial. Van Alstein highlights that, first, teachers need to estimate if the controversy is an open or a settled controversy. A “settled controversy”, for instance, is evolution, which some students may still consider to be controversial. Van Alstein encourages teachers to use correct terminology and to avoid presenting topics in absolutist terms. Instead, it is important to allow students to inquire and learn how to ask disciplinary questions in order to evaluate the topics like a scientist or a historian would. An “open controversy” is a topic that still has unanswered questions within the field. For example, in science classes students may evaluate evidence on effectiveness of different modern vaccines. Dealing with “open controversies” may be more effective for student to engage with once they are accustomed to using the disciplinary methods and weighing viewpoints.

Scenario three: “Controversy as Pedagogy” is where teachers use controversial issues to introduce students to different perspectives and engage students in democratic discussions in the classroom. Prior to using this pedagogy, teachers should plan their goals and preferably have a longer project based time period to work with students. This should be done in an established democratic classroom and it may be better to start with less controversial issues. This way, students would slowly become accustomed to engage with talking about such topics, allowing the classes to be built up to more recent issues or topics closer to their identity. An example from history education could be having students engage in a dialogue or debate on a particular event and look at different historical interpretations. This allows for students to weigh each position and explore why those particular theories may have been held.

In all three scenarios, Van Alstein encourages teachers to use the classroom as a means for democratic engagement by creating a safe classroom with an “open-class climate” in which students and teachers are able to participate in a democratic way. This encourages students to use critical thinking and ask inquiry questions. Such an open class climate can be established if teachers first recognize biases in their own practice and reflect on what their position will be in potential situations. Second, by setting up rules with students to create a democratic, safe classroom. As a teacher, this means some of the classroom authority will shift to students; this encourages self-direction and ownership. Finally, teachers need to help students work through and engage in dialogue around potential controversial or sensitive topics. This may include having students first research or journal their thoughts to ensure a discussion has academic foundation. This may also help students to recognize their own biases and influences of outside narratives.

Expanding into a Broader European Context

The meeting moved forward into each individual or organization sharing their experiences with controversy and polarisation. Participants came from Belgium, Croatia, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and Sweden. Cross-disciplinary discussions between English, science and history teachers along with teacher trainers. It provided rich discussions and best practices to emerge from each context.

Thea, an English teacher from Croatia, described how her school worked to integrate students from Serbian and Croatian backgrounds. The school provides opportunities for students to participate in classes together, in a school system that allows for segregation based upon language. She explained that students have the choice to join in classes or go on trips with classmates from opposite regional identity. This helps in countering stereotypes that each group has about the other.

Olivier, from France, provided intriguing methods using multi-perspectivity in science classes. France has a rigid prescribed syllabi and he has found ways to engage with using the content as controversy, or in Van Alstein’s terms “controversy as pedagogy.” He provided the example of having students research the Human Papilloma Virus vaccine, which is an open controversy with no firm scientific conclusions. Each student group had to present, with evidence, on their recommendations for the vaccine. In one class, three groups, reading the same evidence provided three different answers—one said to get vaccinated, one said do not get vaccinated and the third group said they did not know what to do. The teachers do not force students to select an answer, rather, provide the evidence and allow for students to choose for themselves what they want to believe.

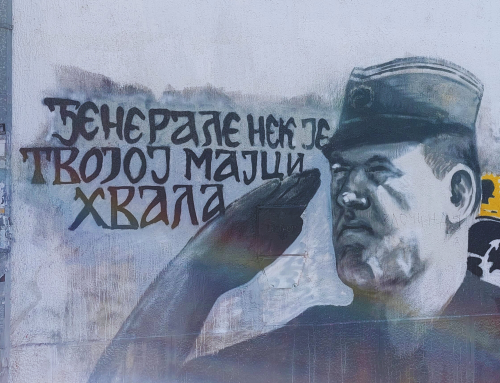

Representatives from Poland and Barcelona discussed the difficulties that teachers, NGOs, and educational professionals are facing in these contexts. In Poland, the discourse is quite bleak around education, with the government vilifying teachers after the month long teacher’s strike. In Barcelona, some teachers are facing the risk of prosecution for discussing the 2017 Catalan conflict after the unsanctioned independence referendum. In both scenarios there is increased fear from teachers and significant blocks for engaging in controversy or polarization in their classrooms.

Despite push back from government and communities there are teachers who encourage students to engage with difficult topics in these contexts. They have created Good Conversation Clubs, Forum Theatre’s and encouraged students to engage with social campaigns. These groups are reaching out to engage with the whole community to initiate whole community change to help restore the loss of trust between teachers and the community. There also is hope in the amount of students that are voluntary participating.

I have done integrated research for my master’s degree and EuroClio. My Master’s research centres on how international school teachers in the Netherlands deal with sensitive and controversial history. I used research and literature to help write a working document for EuroClio on what factors teachers need to consider prior to engaging with sensitive or controversial history. I will share these results via another article that will be published later. EuroClio is working to develop further resources with the Learning to Disagree Project with the March 31 to April 4 2020 annual conference centred on this topic.

Discussions raised question for how controversy and polarization appear in broader European contexts with each organization presenting individuals initiatives and plans. Each country has unique challenges. Despite all of the differences, there are similarities in the ways to go about engaging in difficult conversations or innovative methods using multiperspectivey. The most hopeful result of all is that there are organisations and individuals that are stepping up to the challenges of controversy and polarization in education.

Written By Lexi Oudman, Former Euroclio Trainee