Knowledge and/or Active Citizenship – What does Dutch Youth know about World War Two?

The Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport) is committed to remembrance, research, and education related to the Second World War. On 21 June, it organised a mini-conference, inviting an array of Dutch stakeholders, including museums, archives, research centres, remembrance organisations, and history educators. I also attended this very interesting conference and hereby share my report.

The conference was in fact the launch of a new study, commissioned to the HAN University of Applied Science (based in Arnhem-Nijmgene), led by Dr. Marc van Berkel, which is aimed at helping the Ministry face the challenges of keeping the memories of the experiences of World War Two alive in a society where the eye-witnesses are dying out.

This study (available here in Dutch) puts forward a wide range of research findings. Essentially, around 1200 young people (ages 13-19) were surveyed on their factual knowledge, the sources from which they delve this knowledge, their assessment of these sources, and their attitudes with regard to the history of the Second World War. The survey put forward various names, places, events, processes, and concepts related to World War Two and mainly provides an impression on the state of factual knowledge on this topic.

One by one, representatives of key organizations in this sector commented on the findings:

Kees Ribbens (NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies) commented on the overly positive results of the survey, stressing that the majority of surveyed youth would like to learn more about the topic. He emphasized how the persecution of Jews is much more well-known than other aspects of the war, such as the military aspect, and that the Western European perspective is clearly dominant in the known narrative.

At the same time, he alluded to the conclusion that many concepts (like collaboration, genocide, antisemitism) are much less known. Since two-thirds of the respondents did not answer that it would be better to forget everything about the war, remembrance is actually seen by the youth as very important. He suggested this could also be related to the societal presence of the war as essentially a collective experience and a moral benchmark in schools, museums, and even in public history, including entertainment such as films.

His overarching conclusion drawn from the report, however, was the need for a more critical foundation to enrich this collective understanding. Yes, it seems youth have core knowledge, which is good for keeping the memory of the victims alive, but societal expectations about what is expected to be known about this war is in flux – for example, the need to understand the worldwide historical processes of the war.

Ton van der Schans, President of the Dutch History Teachers Association, VGN) compared this research to earlier research which had also laid bare how much more importance is given to this topic in history education than to any other topic, and within this topic by far most attention is given to the Holocaust. This situation, in his view, is justified by the way in which citizenship, and related values as freedom and justice, is morally benchmarked in The Netherlands with, and through, deliberation on this history.

Van der Schans also wished that the survey would look more into students’ attitudes and historical thinking instead of the focus on factual knowledge. Yet, he also unfolded a plea for storytelling in history education, stating that “We, as a society, need a story, a narrative. This is the way in which individuals can actually be deeply motivated for history.” Building on this, he expressed his wish that teachers would be able to work more with life stories, and local/regional histories, to make sure that the stories told relate well to the students. If students then have a migration background, he stressed, different stories might be needed.

Norbert Hinterleitner (Head at Education Department at the Anne Frank House) shared his optimistic view that these were impressive results and could be taken to be the result of a lot of care and attention for dealing with heritage and remembrance of World War Two. However, he did share his concern that more attention is needed for the wider historical context. While it is laudable that 99% of respondents can recognise Anne Frank from a photo, much fewer respondents can say that she actually came from Germany. He added that the international aspect seems to indeed be quite unknown, as Eastern Europe and Asia rarely feature in the view of history teaching. He also questioned this need by asking: “Even if all this could be provided, should young people be forced to obtain all this factual knowledge? What space is then left for them to interpret it and apply it in their own lives?” He urged therefore, for future studies, and to explore the deeper understanding related to behavioural patterns in society, as well as the value of the rule of law in the context of the protection of minorities: “Will we score equally important high figures? It will show the value of history and civic education.”

Jan van Kooten (Director of the National Committee for 4 and 5 May) also reflected positively on the results of the survey. He discussed in more detail the section of the survey that looked into attitudes – for example, how respondents assessed whether the Second World War is the main influence on the way they think about Freedom (60%), Human Rights (42%), and Racism (34%). He applauded the role of the Ministry in looking at this topic from so many angles and supporting the sector in a broad way, ranging from remembrance to research and education. His key warning, however, was that the survey results may not be able to properly represent all of Dutch society. There seem to be large segments of society which at the moment can hardly be reached. But, with new multipliers, for example, young Dutch rapper Ronnie Flex, with millions of views online, was made Ambassador for Freedom by the committee and this seems to help in reaching difficult target groups.

Kees Boele (Chair of the HAN University of Applied Science) pointed to the fundamental importance of learning history for establishing a personal compass for ethics, which goes beyond the knowledge of facts. He went further to state that this function of education should be made, and seen to be, the very centre of learning. While schools are made more and more to function like factories, and the sector as a whole is seeing education as a feature of the market, with students as consumers of knowledge and teachers as facilitators of learning, he feared that the possibility to think freely in wrestling with concepts of good and evil would disappear. This survey, he held, would need to support that development in education.

Marc van Berkel (Researcher at the HAN University of Applied Science) who led this research stressed the need for more qualitative research to follow up, and – indeed – ensure that empathy, and the ability of people to look beyond their own opinion, should be the prime concern going forward. “It may ultimately not matter if people don’t know who Himmler was,” he continued, “but if they don’t know which activities his policies created, and what kind of trauma these policies left, there is an unbridgeable gap in our understanding of democracy and citizenship.”

The final comments of the day were delivered by Erik Gerritsen (Secretary-General at the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport) who affirmed the current government’s support to the development of historical knowledge and transfer of values. He expressed that the recommendations of the study would be taken into account in the further development of measures to prevent intolerance, and to keep retelling the history of the World War Two, as it uniquely provides citizen’s alertness to learn from the past.

So, what have I made of all of this? Some conclusions:

The report did not make any particular political news. It was ultimately good news, and did not have media-sensitive ‘clickbait.’ It surely will be used as an initial measurement and hopefully can continue to function as this in the years to come.

European partnerships and the work of EuroClio, the Council of Europe, and many European-funded projects and frameworks are completely missing from this national discussion. This is especially problematic and worrying because so much thinking about these issues has already been done and did not seem to really feature. In addition, looking at the way in which Europe struggles with democracy at the moment, it would be good to have more governmental (public) cooperation on these issues happen not only on the cross-border levels, but also be visible on the national stage.

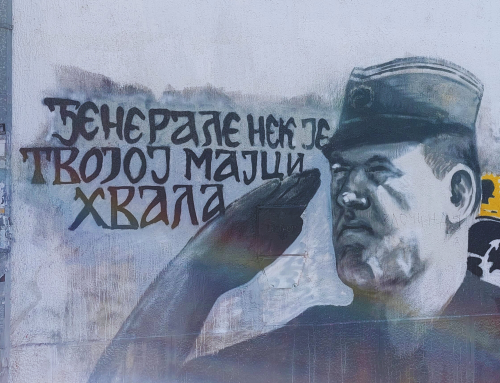

It is good to look into how historical topics which feature so strongly in the collective memory are actually perceived by a new generation of young people. This survey indicated some interesting trends, and it could be very interesting to see how this plays out across Europe, where some very concerning developments can be seen, including revisionism and political flirtations with fascist legacies.

On a more social note, with the exception of the chair of the day, Tasnim Van den Hoogen (Director at the Ministry), all speakers were male, white and ‘of a certain age.’ I admit I only realized this myself when I actually started typing up this report. As inclusion and diversity were mentioned quite a few times, it would have perhaps been good to explore and reflect this in the event itself.